Digital materials

Videos

Podcasts

Digital Books

Image banks

Learning Environments

Annik Gilbert, Conseillère pédagogique au Service national du RÉCIT de l’Inclusion et de l’adaptation scolaire

Isabelle Demers, Conseillère pédagogique au Service national du RÉCIT de l’Inclusion et de l’adaptation scolaire

Martin Gagnon, Conseiller pédagogique au Service national du RÉCIT de l’Inclusion et de l’adaptation scolaire

Marie-Josée Marineau-Harnois, Conseillère pédagogique au Service national du RÉCIT de l’Inclusion et de l’adaptation scolaire

Christine Plourde, Direction des ressources didactiques, des bibliothèques scolaires et des services éducatifs à distance

Geneviève Rioux, Direction des ressources didactiques, des bibliothèques scolaires et des services éducatifs à distance

Thomas Stenzel, Conseiller pédagogique à Learn Quebec

In recent years, the accessibility of resource content has become an increasing concern for those working in the school environment. Initially, the issue was aimed at users of technological aids, but the more these accessibility features are used and applied, the more useful they are for all learners in a classroom.

The intent of this guide is to support school personnel in the selection and production of accessible digital educational resources (ADERs) for learners. In this document, teachers, speech-language pathologists, special educators, and educational consultants are considered to be developers of digital materials.

The first section of this document presents the history of accessibility, and a definition of accessible digital educational resources are provided. In the second section, the elements to be considered in the development of an accessible digital document, namely the principles of universal accessibility, are proposed. Examples, counterexamples and theoretical support will be provided so that the reader of this guide can have a good idea of what each of the criteria implies.

In this way, the reader will be made aware of the importance of the accessibility of documents.

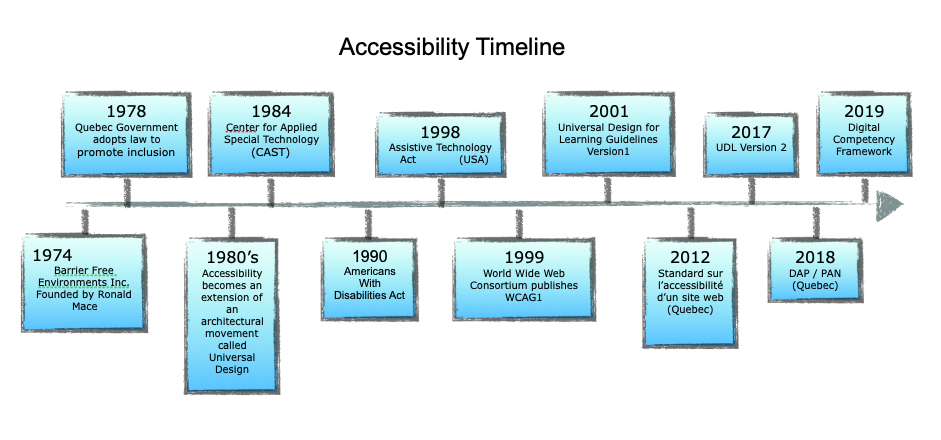

1974: Barrier Free Environments, Inc. was founded by Ronald Mace, an architect, product designer, educator and consultant. He developed the term and concept of Universal Design in housing, products, and architecture, to make these more accessible to people with disabilities.

1978: Quebec adopts a law promoting the inclusion of people with disabilities. This law was amended in 2004 to require government departments and agencies to adhere to WCAG 2.0 standards. An updated reference document was published in 2012.

1980’s: Accessibility becomes an extension of the architectural movement called Universal Design

1984: Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) is established. CAST starts to research and develop the concept of Universal Design for Learning (UDL).

1990: The Americans With Disabilities Act is passed in the USA. The ADA is a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life, including jobs, schools, transportation, and all public and private places that are open to the general public.”

1998: Assistive Technologies Act is passed in the USA. The ATA is “An act to support programs of grants to States to address the assistive technology needs of individuals with disabilities, and for other purposes.”

1999: The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) published the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 1.0 (WCAG10). The purpose was to establish international standards for the World Wide Web.

2001: Universal Design for Learning Guidelines (UDL) version 1 is published. Professional development program for UDL is started.

2012: Standard sur l’accessibilité d’un site Web,

(Quebec). The Conseil du trésor adopted three standards that set out the rules for making any Web site accessible: a standard on the accessibility of a site, a standard on the accessibility of a downloadable document and a standard on the accessibility of multimedia on a Web site. (updated in 2019)

2017: UDL Version 2 is published

2018: the MEES introduced the Digital Action Plan with a $1.186 Billion budget from 2018 to 2023, to accelerate the shift to digital in Quebec’s education system. Measure 01 of the plan was to establish a reference framework of cross-curricular digital competencies at every level of education.

2019: The Digital Competency Framework is published by the MEES. The Framework is an expansion of the CCCs from the QEP. The 12 dimensions of the Digital Competency Framework overlap well with most of the CCCs.

2022: All websites and web content on public school websites must meet accessibility standards.

An accessible digital educational resource (ADER) is teaching and learning material delivered to students in digital form that meets the needs of everyone in an inclusive manner.

An ADER can take many forms: text, images, video or audio. Some of these forms (digital text and images) may be printed to paper after being designed in a digital format. Considering accessibility when creating ADERs will promote better understanding of the content by the user, regardless of the medium.

ADER have great potential in teaching/learning contexts. Among other things, they can meet the diverse needs of all students, including those who are users of assistive technology.

When delivering a document, we want every student to be able to understand its content. Therefore, considering accessibility when creating a document helps to alleviate barriers that students may encounter when reading it (e.g., insufficient contrast, hard to decode font, etc.). While adherence to accessibility criteria may seem demanding, overall it does not interfere with the creativity that can be demonstrated in the production of ADERs.

With the advent of digital technology, the presentation of information has changed: one need only think of the structure of Web sites and interactive documents. Our way of reading has adapted to this new organization of information. In fact, academic research is studying the differences between reading on paper and reading in digital media, which is why it is important to ensure that the materials given to students meet the digital standards for document production.

Below are some articles about dealing with reading on screen:

Reading on-screen vs reading in print: What’s the difference for learning?

Online Reading Strategies for the Classroom

Digital reading strategies to improve student success

Teach students how to read and understand digital text

Here are some pedagogical reasons why thinking about document accessibility is essential for all students:

Digital technology has opened the door to accessibility and provided access to information to many more people. When producing ADERs all twelve dimensions of the digital competency are engaged, but primarily Dimension 7 (Content Production) and Dimension 8 (Inclusion and Diverse Needs) of the Digital Competence Development Continuum are activated. Digital competence is therefore actualized as much in the choice of ADERs as in their production.

This is also true for all students: why not make them aware of the accessibility of their own productions?

Level 1, the minimum accessibility threshold, includes all the criteria that meet the needs of 70% of students with special needs. Compliance with these accessibility criteria makes the text usable and compatible with reading and writing assistive functions. It is expected that, where possible, all ADERs (accessible digital educational resources) will achieve Level 1 accessibility.

Link to interactive version of this section

1.1 Ensure that textual content (eg: texts, tables) are usable and compatible with reading and writing assistance functions

To do this :

1.2 Arrange the textual content in line with the visual content (eg: images, works of art)

To do this :

Level 2, includes additional criteria that make information accessible to 85% of students with special needs. Meeting these accessibility criteria allows students to use assistive reading, locating and navigating features and provides them with alternative options (alternate formats) to access the full content of the resources. Although this level is not mandatory, it is advisable to tailor ADERs (accessible digital educational resources) to meet the criteria of Level 2.

2.1 Ensure that navigation respects the order in which information is presented and is user-friendly

To do this:

2.2 Provide a title and a textual equivalent to visual content (e.g. images, works of art) and audio content (e.g. podcasts, audio books) so that they can be read by text-to-speech and screen readers

To do this :

Level 3, the optimal threshold, combines all accessibility criteria. Compliance with the criteria for this level makes it possible to reach 90% of students with special needs. Regional support persons and educational consultants are the most competent to target the needs of these clienteles and to evaluate the actions to be taken in order to consolidate level 3.

3.1 Determine the reading order of the document (as per level 1)

To do this :

3.2 Offer a textual equivalent (subtitling or transcription) to videos in order to promote access to textual content for not only blind or deaf students, but all who could benefit from these features.

To do this :

Alcott, Lisa. “Reading on-screen vs reading in print: What’s the difference for learning?” (2021), https://natlib.govt.nz/blog/posts/reading-on-screen-vs-reading-in-print-whats-the-difference-for-learning

“An Overview of the Americans With Disabilities Act”, https://adata.org/factsheet/ADA-overview

Brun-Mercer, Nicole. “Online Reading Strategies for the Classroom”, (2019), https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1236175.pdf

CAST, https://www.cast.org/

“Digital Action Plan for Education and Higher Education”, (2018), http://www.education.gouv.qc.ca/en/current-initiatives/digital-action-plan/digital-action-plan/

“Digital Competency Framework“,(2019), http://www.education.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/site_web/documents/ministere/Cadre-reference-competence-num-AN.pdf

Fingal, Jerry. “Teach students how to read — and understand — digital text”, (2020), https://www.iste.org/explore/learning-during-covid-19/teach-students-how-read-and-understand-digital-text

Hopman-Droste, Rachel. “Digital reading strategies to improve student success”, (2022), https://www.pearson.com/ped-blogs/blogs/2022/01/digital-reading-strategies-to-improve-student-success.html

“Public Law 105 – 394 – Assistive Technology Act of 1998”, https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/PLAW-105publ394

“Ronald Mace”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ronald_Mace

SECRÉTARIAT DU CONSEIL DU TRÉSOR (2012), « Standard sur l’accessibilité d’un site web, (SGQRI-008-01) », https://www.tresor.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/PDF/ressources_informationnelles/AccessibiliteWeb/access_web_ve.pdf

SECRÉTARIAT DU CONSEIL DU TRÉSOR (2019), « Standard sur l’accessibilité des sites Web, (SGQRI 008 2.0) », https://www.tresor.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/PDF/ressources_informationnelles/AccessibiliteWeb/standard-access-web.pdf

“Web content accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1”, (2022), https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/

Links to:

Guide pour la production et pour le choix de ressources numériques accessibles

Service National Inclusion et Adaptation Scolaire

PDF of this web section: A Guide for the Production and Selection of Accessible Digital Resources

© 2024 LEARN. Tous droits réservés